Assessing Venture Capital Fund Investing as an LP

Disclaimer: All views in this article are my own, and I do not intend to represent any organization with my thoughts in this article. Any information provided on this website does not constitute investment advice or investment recommendation nor does it constitute an offer to buy or sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell shares or units in any of the investment funds or other financial instruments described on this website.

How do LPs think about investing in venture capital funds? I have crystallized some of my personal thoughts below based on my learnings so far being on the LP side.

This post will be go over the following topics:

How Venture Capital works

Why Venture Capital matters

Venture Capital's role in a diversified portfolio

How to select Venture Capital managers

Overview

What is Venture Capital?

Simply put, venture capital is a type of investment raised by startups for the sole purpose of funding growth.

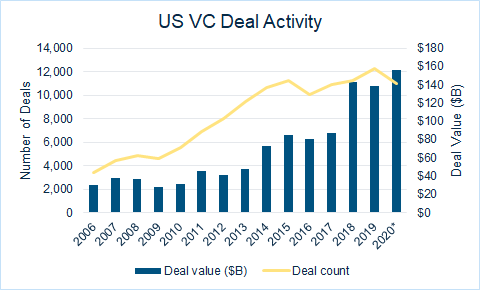

The chart below sums up the size of the US venture capital landscape pretty well. Deal value below indicates the total amount invested by venture capitalists into companies. Deal count indicates the total number of companies invested in by venture capitalists.

Venture capital investing can be divided up into three main stages:

Angel and Seed stage

Early-stage

Later-stage

Why are there different investment stages? Investing in startups is very risky, and so investors want to know the level of risk they are taking on when investing in a startup. For example, if you invest really early in startup X (i.e. two kids in their college dorm room) you are taking on a lot of risk. Compare that scenario to investing in startup Y that has customers, already has revenue, and has a larger team. Investing in Y still has risk, but it is less risk than investing in X. This difference in risk is why investors have separated investing in startups into three different stages. As a startup grows and increases its customer base, there is less investment risk from the point of view of an investor.

Why Venture Capital Matters

A Stanford paper released in 2015 outlined the value of venture capital to the US economy. A few summary statistics from the analysis are detailed below:

Post-1979, 43% of the companies that were founded that went on to go public were VC-backed

VC-backed public companies now account for 42% of total R&D spending by all public companies

Over the past 50 years, the U.S. VC industry has raised $0.6 trillion, while the traditional private equity (buyout) industry has raised $2.4 trillion

VC-backed public companies employ more than 4 million people

The statistics are helpful, but why does venture capital really matter?

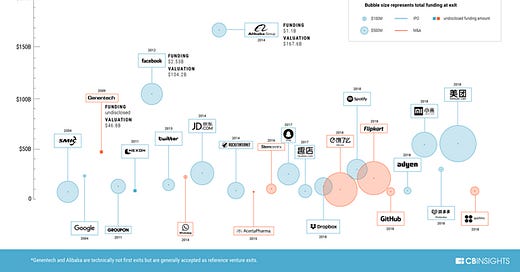

Venture capital matters because it allows people to truly innovate, break boundaries, and build new things that can significantly improve people’s lives. Over the past few decades, the category defining companies have been funded by venture capital, such as Airbnb, Google, and Uber. These companies have produced enormous returns for venture capital funds, which is what makes investing in startups attractive. A few notable examples of the largest venture capital exits can be seen below:

How Venture Capital Works

Fund Structure

The below graph sums up the legal fund structure of a venture capital fund:

Let’s try to understand how the above (seemingly complicated) structure works through a story. Bob lives in Silicon Valley. Bob has many friends who have their own startups. Bob believes he can invest in a few of his friends’ startups and make a lot of money. Bob only has $2 million of his own, but to invest in at least 10 startups, he needs $50 million. Where will he get this money? Bob decides to talk to Sam, someone he knows at XYZ Pension (a pension fund gets money from people when they are young, invests it, grows the money, and pays out the money to the people when they are in retirement). The XYZ Pension has $5 billion, and they want to invest in startups, but they don’t know how to, so they accept the meeting from Bob.

Bob tells Sam that he has friends that have startups and that Bob can invest in their startups. Sam from the XYZ Pension is excited because the pension fund wants to grow their money by investing some of their money in startups but they don’t know how to do so. Sam decides that he can give Bob the $50 million from the pension fund, Bob can invest it in startups, and then hopefully that money will grow overtime. Bob estimates after 10 years he can give $100 million back to the XYZ Pension. Sam is ecstatic because he thinks that Bob can double the Pension’s $50 million.

Bob then creates his venture capital company (called the General Partner, or GP, shown by the red box above) and he is the sole owner of this company. However, to take the Pension’s $50 million, Bob needs to create a fund, so bob creates a venture capital fund (blue box) with the help of a lawyer. Once Bob creates this fund, the Pension wires his fund the $50 million. Now Bob has $50 million to invest in his friends’ startups!

The above example illustrates effectively how a venture capital structure is formed and who the investors are in a venture capital fund (in the above case, the XYZ Pension).

Mechanics

There are a few things to note about venture capital funds from a legal standpoint. Usually, funds have finite lives (unlike mutual funds, for example). Most venture capital funds have a fund life of about 10 years. However, many funds technically exist for longer than 10 years because it can take many years to exit a company and return the capital to investors. Overall, fund life can be separated into four main phases:\

Formation: In this stage, the partners of the GP (in the above case, this would be Bob) set up the actual fund, do all the paper work, find Limited Partners (in the above case, this would be the XYZ Pension), and actually get the dollars from the Limited Partners (LPs).

Investment: Once all the legal work is done, and the GP actually has the money from the Limited Partners, it is ready to invest in companies. The investment period is usually defined in the paper work in the formation stage and is an agreed upon period of time by both the LPs and the GP. This period of time is usually 3-5 years and this is usually the most labor-intensive part of the entire investment process for the GP, as it has to find companies to invest in. During this stage, a venture capital fund usually “reserves” a certain amount of money for expected follow-on financings. We’ll discuss this again below.

Harvesting: After the investment stage is complete, the GP is done making initial investments. During this stage, the partners of the private equity fund help their companies (termed “holding companies”) in any way they can to grow further. In venture capital, during this stage the GP may have to invest further in their holding companies. Why? This can be explained through an example below.

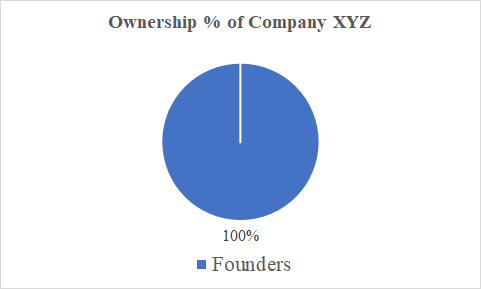

Say there is a company setup by two founders (Company XYZ). The company is 100% owned by the co-founders at this point.

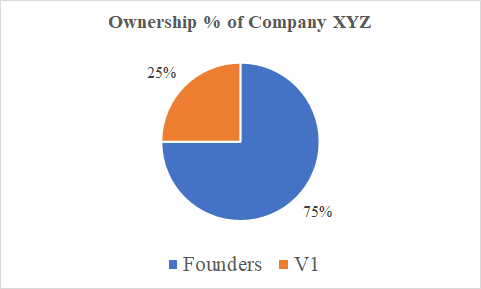

After some time, company XYZ needs money from venture capital investors. A venture firm (V1) invests in Company XYZ in exchange for 25% of the company. After this investment, the ownership of the company looks like this:

The ownership of the founders has been reduced from 100% to 75%. This is called “dilution.” Sometime further in the future, Company XYZ needs more money, so another venture capital firm comes in to invest money (V2). This fund invests money into the company in exchange for 20% of the company. What happens to the ownership of the first venture investor (V1) and the co-founders? It gets reduced by 20% because they have implicitly “sold” 20% of their respective ownership stakes to the third investor (V2). For example, V1’s new ownership = V1’s old ownership (25%) x (1 - 20%).

Bringing this back to the fund mechanics, effectively fund managers want to avoid getting their ownership reduced in their companies (what happened to venture firm V1 above) by new investors, so they “reserve” a part of the money given to them by LPs to invest in their best companies so that they maintain their ownership in these firms.

Exit

So the venture capital fund invests money into companies, but how does it exactly make money? The fund makes money when other investors buy their shares from them at a higher price than the price they paid (just like the stock market). This can happen in two ways:

Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A): in this case, another company (usually larger) acquires or merges with a venture capital fund’s holding company. In this case, the acquiring company pays money to buy the holding company, and the venture fund receives its pro-rata amount (amount paid to acquire the company x equity ownership %).

IPO: in this case, the venture capital fund’s holding company goes public and lists on the stock exchange. During this process, the venture capital fund can sell its private shares to public market investors.

The discussion below on fees will specifically outline how both the GP and the LP make money.

Fees

Management Fees

In the venture capital industry (and in private equity in general), the GP requires that the LP pay them a certain fee every year for managing the money and investing it in companies. This fee is usually used to fund expenses such as salaries (people who need to go out, find companies, hire lawyers to sign the paper work to invest in the companies, etc.) and other back office functions like accounting. This fee is called the management fee. It is usually 2% of the total fund assets.

Carried Interest

The second type of fee that GPs receive is called the “carried interest” or “carry.” This type of fee aligns the incentives of the LP (the institutions providing the money in anticipation of return) and the GP (fund managers who want to use their expertise in investing to make money). Effectively, the GP earns a carry if it makes a profit on its investment. A simplified example is provided below:

Example: A venture capital fund (Fund XYZ) has $100m in its fund contributed by LPs. It invests in company A for $20m. 7 years later, Fund XYZ sells its investment in Company A for $100m. This is a 5x return. First, Fund XYZ usually returns the invested amount to the LP at no charge (this would be $20m in this case). Any amount above the $20m is profit, which is $80m in this case. Of this $80m, a pre-set percentage is rewarded to the fund managers (this % is set in the formation stage of the fund life cycle). Usually, this is 20%, so in this case the fund managers would get 20% x $80m which is $16m and the LPs would get the other $64m. The breakdown of returns can be seen below:

“Gross” return is defined as the return that the LP has on “paper” before paying the GP carry. This is the $100m that the company was sold for divided by the initial investment in the company ($20m). However, the LP doesn’t actually get a 5x return because it has to pay 20% of the profit to the GP (deservingly so, since the GP found the company and did all the work to invest in it). So the “Net” return is after the LP has paid the GP carry, which is the actual return, in this case 4.2x. There are a lot more details when it comes to carry, but they will not be covered in this post.

Venture Capital's Role in a Diversified Portfolio

As an investor who does not want to put all their eggs in one basket, the real question is: how much of your portfolio should be in venture capital? All large investors such as pensions, endowments, and foundations have to wrestle with this question.

Fundamentally you want to answer this question from the perspective of "how much are you willing to lose?" In other words, you need to think about risk. A helpful framework from the Wealth Management world can be seen below:

As an investor, you need to assess yourself on these three criteria to determine how much to put into risky assets (public equities, private equity, etc.). There are many methods for doing this, but one method is to do a wealth management survey which will output a numerical score for each of these criteria.

Effectively, if your ability to take risk is high (long time horizon and you have a lot of current liquidity or cash), your willingness to take risk is high (how much money you are willing to lose), and your need to take risk is high (you need to hit a high return number for your portfolio), having a material portion of your portfolio in venture capital makes sense.

Next, you would so some sort of portfolio optimization math to figure out exactly how much of your portfolio you should have in venture capital. This is based on how much you as an investor should expect to make by investing in venture capital and other asset classes.

What is an Appropriate Expected Return in Venture Capital?

To determine how much you expect to return on an annualized basis from venture capital investing, you must determine your hurdle rate for investing in this area. To determine this, one methodology called the “building-block” approach can be used. This approach effectively says:

The return I expect from venture capital (say in the US) should equal the return I expect from investing in large US companies plus the return I expect to compensate me for locking up my capital for 10+ years plus the return I expect to compensate me for taking the risk of investing in small startups

This can be visually seen as follows:

This intuitively makes sense: you expect to make more money investing in venture capital than by investing in large established businesses (yellow box, such as Coca Cola) because you are taking on more risk by investing in venture capital. You are also locking up your money when you invest in a venture capital fund (you may not get back money until 10 years in the future) and this is another risk because if you need money between now and the 10 years, you won’t be able to take it out of the venture capital fund.

To actually determine the numerical percentage annual return is out of the scope of this post, but if most people expect to earn 7-8% a year by investing in the stock market, a return of around 17-20% is not unreasonable to expect when investing in venture capital given the increased risk. Over a 10 year fund, this equates to about a 3x return on capital (before fees). In other words, if you invest $100 in 2010 in a venture capital fund, by 2020 you should expect to receive $300 (this is an oversimplification since usually the fund will exit some companies in less than 10 years and some companies in greater than 10 years).

Now, the real question is, how probable is it for me, as investor to earn this 3x return (just to keep it simple, before fees) when investing in venture capital?

The Distribution of Venture Capital Fund Returns

A distribution of returns lays out all the annual/by fund returns of an asset class so that an investor can understand what’s the probability they will earn a specific return in any given year/fund. For example, the annual return distribution of the S&P 500 index is shown below:

The return distribution resembles a normal distribution, and this helps us understand what we can expect our future distribution to at least resemble. For example, we see that there are very few situations where the market has a -30 to -40% return on annual basis, which means we can expect this to happen in rare situations such as an economic collapse/recession.

There is also data to help us understand the distribution of venture capital returns. The returns of venture capital funds are influenced by the underlying returns of the companies they invest in. We can first try to understand the distribution of the underlying holding companies.

Return Distribution of Realized Venture Outcomes

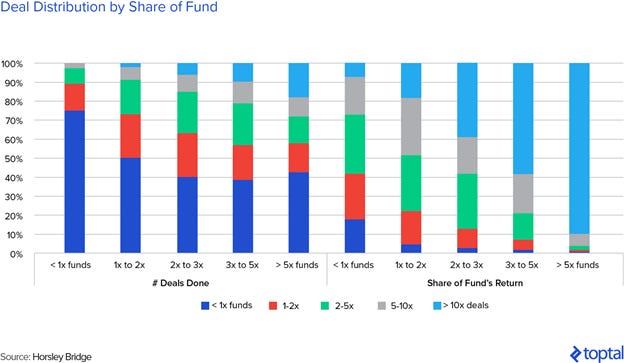

The above chart shows the distribution of returns by investing in US startups between the years of 2009 and 2018. We can clearly see that most startups lose money (about 64% of the time), while very few startups return a 10-20x multiple (3% of the time). This is referred to as a power-law distribution, where a small percentage of startups make up most of the returns generated by investing in this space.

So clearly, you want the venture capital fund you are investing in to be able to get those 10-20x or more outcomes (the Googles and Facebooks of the world), but how probable is this?

Return Distribution of Venture Capital Funds

There is some data on the return distribution of the venture capital funds themselves. The California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS) is an active investor in venture capital funds (it is an LP, as we defined earlier), and publicly released data on 135 venture capital fund investments between funds that commenced between 1999 and 2009. The distribution of returns can be seen below:

The above graph shows that the average multiple return by investing in venture capital funds is about 1.6x, a far-cry from the 3x that we require (over a 10 year period). This means there is a mismatch between what we expect and what venture capital funds actually return. We can further solidify this point by trying to model a venture portfolio.

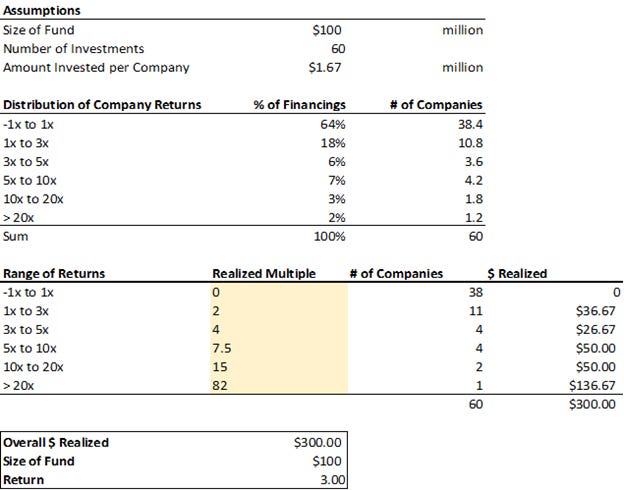

Modelling a Venture Capital Fund Portfolio

A very simplified model of a venture capital portfolio can be seen above (doesn’t include follow-on financings and dilution, etc.). The yellow highlighted region is where we can input what the realized multiple will actually be of the investments in each bucket of returns (based on the distribution shown above). Overall, we can see that to get around a 3x (gross) return, the venture capital fund must find a “home-run” investment. Without the homerun, the return looks like this:

In the above case, the homerun investment makes or breaks the fund. This is also evident in the real-world, where 6% of all venture deals make up for 60% of the industry’s returns. This is further validated by the below chart by Horsley Bridge which shows that for funds that had returns above 5x, less than 20% of deals produced 90% of the fund’s returns.

So is it all about having enough “shots on goal” so that you are maximizing your chance of hitting a unicorn?

Not quite. It is a chicken-and-egg problem, because as you increase the number of investments in the fund, more companies will fail and your homerun investment will have to return more money to compensate for the increased losses. For example, using the same model above, if we increase the number of investments to 60 it results in the following output:

The amount in each investment goes down, but the realized multiple on the homerun investment (>20x investment) needs to be much higher to make the fund have a realized multiple of 3x. Again, this is a simplified approach to modelling a venture portfolio because ideally you would want to model the follow-on capital invested at later rounds into the one company that is a greater than 20x, but the key insight is to get a 3x multiple on the fund, a venture fund does not only have to have enough shots on goal, but it also needs to make sure it does not “over-diversify” such that it becomes too hard to get to the 3x target return.

This leads us to our next question: as an LP, 1) how do you structure a VC portfolio, and 2) how do you select the VCs that will have the highest chance of returning a 3x?

Building a Venture Capital Fund Portfolio as an LP

Structuring a Venture Program

As an LP, there is a choice to make:

Either have many venture funds in the portfolio, which allow for many shots on goal, and invest a small amount with each one

Or have a few venture fund investments in the best brand/highest quality funds

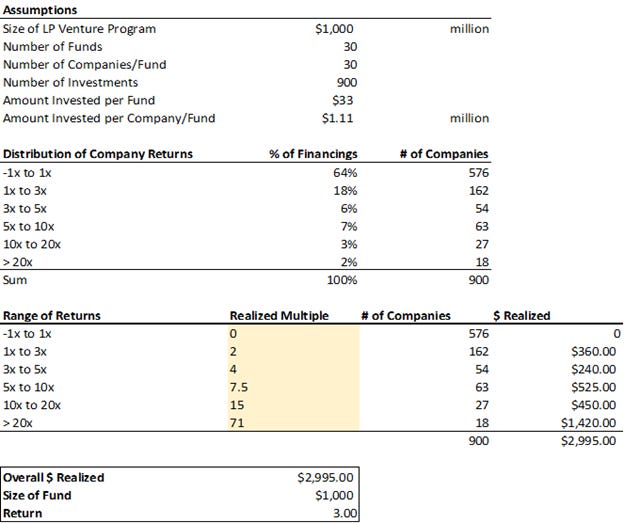

The problem with a “splatter” approach where an LP would invest in many venture funds is that it results in an over-diversification problem. For example, if an LP had $1B allocated to venture capital and it had 30 funds at an investment of ~$33m per fund, and each fund had 30 holding companies, that is an exposure to 900 underlying companies. For the overall venture program to return a 3x, there would have to be at least 18 companies that have a ~70x return in the entire program. Given the distribution above, this seems probable (just apply the 2% probability of > 20x return). However, what does this actually mean?

The below model shows the LP Venture Program model:

What we have to understand is this is implying that the venture program is involved in around 18-near unicorn companies. This is because if the post-money valuation of each company at investment time is about $11m ($1.11m invested / 10% average ownership), a 70x multiple would mean the company is reaching almost unicorn status at exit. For an average LP to expect their venture program to result in 18 unicorns over 10 years is possibly a stretch.

Conclusion: It may be a more realistic approach to have a concentrated group of venture managers. This is because the point of venture in a portfolio is not to diversify the portfolio or dampen volatility, it is to generate strong multiples. Having a very diversified portfolio of venture managers makes this harder to achieve because as you increase the number of managers, the chance you get a mean return goes up and mean venture returns are not attractive (as we’ll look at in the next section).

Venture Capital Fund Returns - Is it Worth It?

So is venture even worth it from a portfolio perspective? It gets all the hype these days, let’s see if it has delivered.

The Kauffman Foundation has been an LP in venture capital funds for decades. It’s asset base today stands at about $2.6 billion. In 2012, the Foundation released a report that outlined key lessons from its twenty years of venture capital fund investing, during which it invested in over 100 venture capital funds. The key insight was: firstly,the average VC fund fails to return investor capital after fees and secondly, most venture capital programs do not produce returns that exceed the public equity benchmark by 3-5% a year. In other words, the average VC fund produces no returns (returning capital means a 1x return).

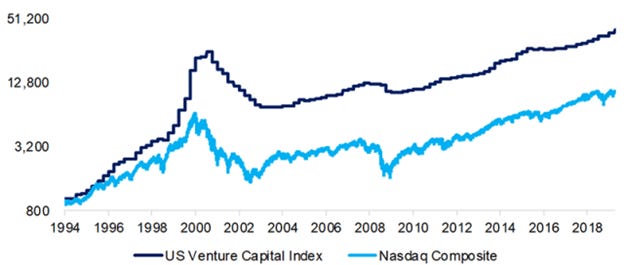

Investing in venture in the early to mid-1990s generated strong returns that beat the public markets. However, after that period, returns have not been able to beat the public markets (NASDAQ):

Most of the outperformance versus the NASDAQ happened before the burst of the Tech Bubble. After that point, returns have not kept up with the public market index.

As mentioned in an above section, an investor should at least expect venture capital funds to produce better returns than the public market alternative since VC funds lock up capital for at least 10 years whereas investing in the public market allows investors to buy and sell at any point. The Kauffman Foundation also concluded that only 16 of the 100 funds they invested in generated a return of more than 2x, while the rest underperformed dramatically, resulting in an overall return of 1.31x for the entire venture portfolio over their time horizon (a far cry from the required multiple of about 3x as mentioned above).

The Kauffman Foundation’s overall return was actually on the high end compared to other LPs over the same time period, further indicating the challenges of hitting the 3x multiple on a venture program.

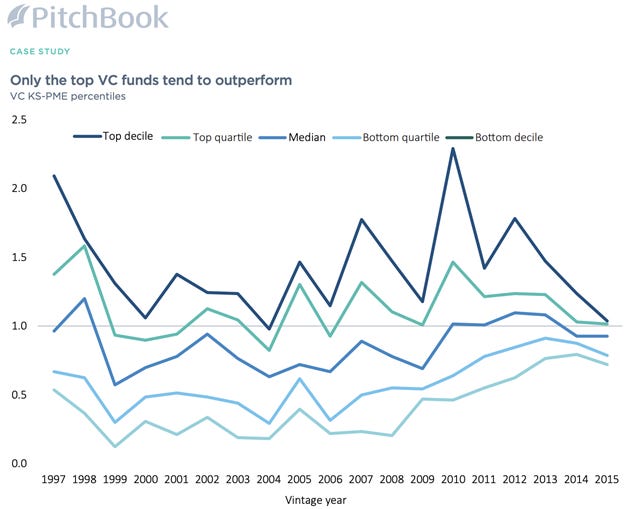

Another way of viewing the same data is to look at the KS PME metric (Kaplan-Schoar). As explained on Pitchbook.com:

“The results of the calculation are straightforward; If the end value is higher than one, then the private market fund has outperformed the respective public market index and if it’s lower than one, it underperformed.”

It is helpful to use the KS-PME metric because to assess private equity performance because it does not use IRR, which is a commonly cited metric by venture managers, because IRR can be easily manufactured due to its sensitivity to cash flow timing. The below chart shows the KS-PME for venture funds by vintage year by percentile, and also indicates that the median fund does not outperform the index, which in this case is the S&P 500:

In other words, the median venture capital fund doesn’t do well. Only a select group of managers in the top quartile and top decile outperform.

This leads us to a key question:

Which types managers are in the top quartile and decile? In other words, can LPs predict which managers will outperform the public market alternative?

What Matters in Venture Capital

The above analysis indicates that investing in venture capital funds only makes sense if one can invest in the top funds. As the Kauffman Foundation points out:

“VC Returns typically are concentrated in only ten to twenty partnerships out of hundreds competing for investor capital, and that elite group of investment managers can disproportionately impact average return results for VC funds as a whole.”

Is this as simple as investing in Sequoia or Andreesen (top venture capital firms)? Not necessarily. For one, emerging and new managers have been generating an increasing percentage of venture capital gains overtime, as shown by the below chart:

Okay, so if both emerging and established managers can generate attractive returns, then what predicts venture fund outperformance? To understand that, it’s important to understand what drives the outlier returns for venture capital funds.

To understand what drives returns in venture capital, we have to try to understand what separates the homerun companies from the ones that are not.

There is an ongoing study by CB Insights which has a database of 240+ post-mortem letters from entrepreneurs and why their businesses failed. The main reason why is product-market fit.

The second main reason is lack of cash, and the third main reason is inappropriate team.

Starting with the first problem, what does product-market fit mean? There are a variety of definitions, and many VCs have written about this in the past but it is really: does the product provide significant value to a subset of the population (customers segment) and can the company communicate that value to the potential customers?

In other words, it’s about product and distribution. However, you can only build a product/distribution if you have the team with the right skillset, passion, and experience. So the main factors seem to be:

1) How strong is the founder/team for the type of business they want to create. This influences what is in the founder’s control: product and distribution.

2) The market the founder is trying to go after.

3) Whether the founder can provide enough value to the customers in the target segment (product-market fit).

As a venture capital investor, it’s important to be able to assess product-market fit, and be able to invest in the best founders building category-defining companies. To put it simply, it’s about 1) having the network to be able to invest in the best founders, and 2) assess which “areas” are worth going after.

Not all venture capital investors had access to SpaceX’s early funding round. Only the ones that had personal relationships with Elon Musk or truly believed in his vision were able to win the deal and invest in the company.

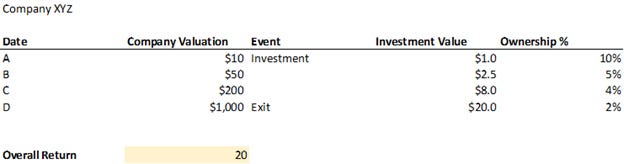

The third variable is whether the venture fund is able to “pull-the-trigger” on the highest conviction investments. This is because continuing to back a successful company to maintain ownership % (avoiding dilution, as discussed above) is not easy for most venture investors because it results in some form of concentration, the antithesis of conventional venture investing (many bets, few wins). For example, in the model investment below, a fund below invested in Company XYZ at a valuation of $10m and received 10% ownership. This company ends up being a home-run, with its valuation going up 100x, but the fund’s ownership gets diluted from 10% to 2%, dampening its return to a 20x, which is still a homerun but may not be enough if the fund is extremely diversified. The venture fund could have done a better job in making sure it was a significant investor in later rounds. This would have resulted in a higher overall return for the fund. However, this requires 1) preferential access since the founder of the startup should continue to want the venture capital firm to be an investor, and 2) conviction from the venture capital fund to size up the position.

A paper published in the Journal of Financial Economics titled, “The Persistence Effect of Initial Success: Evidence from Venture Capital” noted:

“We find that initial success appears to depend in large part on being in the right places at the right times. VC firms, however, do not appear to have any ability to select those attractive segments on a consistent basis. Differences in the selection or nurturing of specific portfolio companies also appear to contribute little to explaining persistence. Overall, our results appear most consistent with performance persistence in venture capital arising from differential access to deal flow for VCs whose initial investments were more successful.”

Firstly, it’s important to point out that initial success matters in venture capital. This is not intuitive, because initial success in public market funds does not predict future returns (correlation of close to 0). In venture capital, on the other hand, the correlation between future fund performance and historical fund performance can be as high as 0.7.

There are two key implications from the above analysis:

1) What matters the most in venture capital is deal flow, or the ability to invest in the best companies

2) Success begets success because initial success results in preferential access going forward.

Yet again, a further question arises: what predicts initial success?

Using data analysis, the paper mentioned prior concludes that initial success is based “almost entirely” on investing in the right segment at the right time, either by chance or by the ability to anticipate emerging trends. Interestingly, the paper also noted that VCs that invested in attractive segments in the past had no consistent ability to do this going forward.

Going even deeper, the outperformance and performance persistence seems to lie not only with specific venture funds, but also with specific individual partners. A paper published in The Journal of The American Finance Association noted:

“We find evidence of skill and exit style differences even among venture partners investing at the same VC firm at the same time. Furthermore, our estimates suggest the partners' human capital is two to five times more important than the VC firm's organizational capital in explaining performance.”

This may also explain why emerging managers have been producing a greater share of the returns over the past few years, since partners regularly leave a venture capital firm that they were successful in to start their own fund.

The last point to note is that there is strong evidence of mean reversion of returns for VC funds who have had strong performance and performance persistence overtime. Several papers, such as Harris et al (2014) and Nanda et al (2019) have concluded this. This could be due to the following reasons:

Size: Initial success begets further success, which attracts further investors and an attractiveness to larger funds (more fees for the GP)

Partner Attrition: As we saw, most of the venture capital fund outperformance can be attributed to specific partners within a fund, and sometimes partners leave and start their own fund.

The point on size is also supported by evidence. As the Kauffman Foundation notes, “we have no funds in our portfolio that have raised more than $500m and returned more than 2x our capital after fees.” This makes sense because the larger the fund, the larger the check sizes, and the larger the companies need to exit at to deliver a 3x return. For example, for a company valued at $10m to return a 50x, it needs to get to a valuation of $500m. On the other hand, for a $500m valuation company to deliver a 50x, it needs to get to a valuation of $25 billion. Larger companies attract more competition, and more competition dampens profits and therefore puts an upper cap at the size of company size.

How Can LPs Stack the Odds in Their Favor?

Now that we have established what matters in venture capital (to deliver outperformance), how can LPs who want to build a venture program actually execute and stack the odds in their favor?

First, it would be summarize everything mentioned above to evaluate all the different “flavors” in venture capital fund investing from an LP’s perspective.

Different Types of Funds to Invest in and Their Characteristics

The rows:

Emerging Partner: a partner who does not have past success in venture capital (i.e. first-time venture partners). These could include academics, entrepreneurs, and so on.

Emerging Fund: a partner who has had either only initial success or initial success and persistent success in venture capital investing, usually at a more established firm but now has started his own firm.

Established Fund: a fund that has many partners and has been around for a long time. Usually this fund has had initial and persistent success overtime, which has led to larger fundraises.

The columns:

Startup Risk: the fact that there is some risk in starting a new firm. Emerging partners and funds have to figure out how to hire analysts, build the operations, raise capital, etc. Further, sometimes emerging funds/partners team up with partners from other firms for the first time, and there is some risk involved because sometimes people don’t get along with each other.

Generational Planning Risk: this is the risk that since partners are getting older, they need to appoint younger partners as the leaders of the firm going forward. This is usually high for established funds because they have been around for a long time.

Probability of LP Access: this is the chance that a LP building out its venture program for the first time can have access to the fund. For emerging partners/funds who need capital and new LPs, the chance that a new LP can commit capital here is higher. For established funds like Sequoia who have relationships with LPs for many years (sometimes decades) will probably continue to take the capital from those LPs going forward as well.

Level of Reversion to the Mean: this is the level of mean reversion the fund’s performance is likely to experience going forward. For a newer fund, the chance of this is low because usually these funds are smaller and the differentiated access is likely still present. For an established fund with partner attrition and larger fund size, the level of reversion to the mean going forward is likely high.

Summary

To summarize:

Venture capital funds have raised more capital and larger funds over the last 20 years as companies have opted to stay private longer and raise funds at larger private valuations. Continued monetary easing and lower interest rates have also pushed more institutional investors (endowments, pensions) to invest in riskier asset classes, such as venture capital, further increasing fund sizes.Venture returns both on the company-level and the fund-level are power-law distributed. For contrast, public market returns are normally distributed.

All that matters in venture is not the amount of losses in the portfolio, or the average return of the companies. It’s all about home-runs.

Overtime, the mean/median return in public markets is around 6-7%, while it is much lower for venture capital funds. This is counter-intuitive, since one would expect venture capital funds to deliver higher returns given the higher risk (investing in startups) involved. This is further evident by the fact that median venture returns have not kept up with public market returns (NASDAQ, S&P) over the past 20 years.

However, the dispersion in performance across venture capital funds is high, meaning the top funds significantly outperform both the bottom funds and the public market alternative. This is where attractiveness of venture capital lies.

What are the characteristics of these top venture capital funds? It’s mostly about access so that the fund is able to invest in the best founders and their companies.

One has to zoom in even further, to a partner-level, where is also significant dispersion even intra-firm. These successful venture funds have partners who have had initial success by investing in companies in “breakout segments,” which has resulted in them getting preferential deal flow going forward, and therefore continued outperformance on their deals relative to peers and public market returns.

The venture partner either got that initial success through luck, or by identifying which segments were going to breakout. Either way, the home-runs that they invest in successfully achieved product-market fit.

An LP can invest in these top partners by either backing them 1) before they get initial venture capital success (emerging partner), 2) after they’ve gotten venture capital success at another firm and have left that firm to start their own fund (emerging fund), or 3) by backing established venture capital funds that house successful partners (i.e. Sequoia).

Lastly, in constructing a portfolio, an LP should consider the “full-stack” of investing, including across stages, and not “pigeon-hole” themselves in a specific stage.

LPs can invest in 1) unproven investors in unproven areas, 2) unproven investors in proven areas, and 3) proven investors in proven areas. The one they should re-consider and dig deeper into are 4) proven investors in unproven areas as this approach has not resulted in performance persistence, even if the firm has had success in a prior area (i.e. a fund that has had success in software raising a new biotech fund). Areas can either be industry segments (biotech, hardware, software) or regions (China, India, South East Asia).

What LPs actually invest in depends on which funds they can get access to, their level of risk tolerance, and their understanding of the area they are investing in.

Preferably, an LP should only have a few relationships (concentrated approach). A smaller (and more diversified) part of the portfolio can be further optionalized, which would consist of unproven partners who have not had initial success but are operating with an edge in a new area (unproven area) such as a new region (South East Asia) or industry (hardware).

Lastly, to differentiate between luck and skill, an LP should assess the venture manager’s 1) network within the area they had initial success in, 2) assess the manager’s deep knowledge in the area they have expertise in. This should allow the LP to differentiate between managers who had the initial success due to luck versus skill. References with entrepreneurs and other investors in the area to determine the venture manager’s reputation are also key.

https://nvca.org/research/pitchbook-nvca-venture-monitor/

https://www.cambridgeassociates.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Venture-Capital-Disrupts-Venture-Capital.pdf

https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2020/02/26/the-persistent-effect-of-initial-success-evidence-from-venture-capital/

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jofi.12249